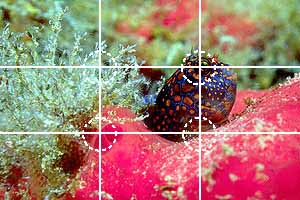

The Basics of CompositionThere are really only a few rules in composition, and even those rules are malleable. I tried to distill the basics down to three easily-remembered rules, but it's not quite that easy. However, I did manage to get it down to three basics and a few assorted small suggestions/recommendations. Here goes. 1. Feature the subject.Every picture has to have a subject--the subject is what makes the picture interesting. If your viewers can't figure out what the subject is, your picture has basically failed. The subject should, in most cases, just about grab the viewer's eyeballs and shout into their ears "I'm the subject! Look at me!" You, as the photographer, have the job of making sure the subject does that. Sometimes that's an easy task; a whale shark in blue water is hard to miss. Other times, it's more difficult; a camouflaged creature can be difficult to pick out from a busy background.

There are several parts to featuring the subject. First off, when you're framing up a picture, make sure that the subject is a sizable portion of the frame. I'd say that one quarter to one-third of the frame is sort of bare minimum. There are exceptions, of course, but 1/4 to 1/3 is a good rule of thumb. Next, be wary of coral or sand backgrounds for your subject. Blue water is much better. That's not to say that you can't have coral in the picture, but it's generally better to have your subject above or next to the coral, with blue water behind it. A very easy way to avoid cluttered backgrounds is an often-repeated rule for underwater photography: shoot from below your subject, aiming up towards the surface. Of course I'm not suggesting you take pictures of fish bellies, so don't over-emphasize this rule. Just a few degrees of incline below your subject is all it takes. There are other reasons for shooting upwards, including getting brighter water for a background, taking advantage of surface effects, and the observation that it's easier to approach fish from below. Lighting is also an important part of featuring the subject, but the details of lighting are another subject for another section. Just remember to light your subject appropriately. Finally, there's a very important rule for featuring the subject: make sure that you can see the subject's eye, and that it is in focus. "Eye contact" with the viewer is essential. Whether shooting fish, octopus, turtles, or people, the eyes have it. If your viewers can't see the subject's eye, they won't have good contact with it. Just having the eye visible is not good enough; you must ensure that the eye is in sharp focus. There's only one reliable way to do this: focus on the eye, every picture, every time. If you can focus on it, you can see it. You've killed two birds with one stone by remembering that rule.

3. Beware of LinesLines are a powerful feature in any photograph. They draw the viewer's eye along the line, and then the eye keeps travelling past the end of the line. But lines can be a bad thing, too. Specifically, vertical and horizontal lines often add an element of symmetry that is comnpletely undesired. Unless you're photographing a man-made object or the horizon, you probably want to avoid horizontal lines. If there's a line of some sort in the photograph, you're probably best off arranging it to be diagonal. Here are some examples of good and bad use of lines.

| |||||||||||

About | UW Photos | Scuba Picture Uv the Day | Flower Gardens | Aquashot | Trip Reports | RSDiver | Photo Instruction | News | Desktop/Screensaver Images | Site Map |

||